Cinematic Ghosts

On Christoph Girardet and Matthias Müller’s Misty Picture

At the beginning of the 2000s, my family’s favourite pastime was watching movies—nothing unusual in a country where the newly arrived commercial television stations flooded the screens with American blockbusters of the 80s and 90s. During the previous decades of dictatorship, most of these productions remained largely unavailable to Eastern audiences. But this was the new millennium, and by watching those pictures, an entire generation learned to dream of skyscrapers, malls, and picturesque suburban houses surrounded by evergreen lawns—signifiers of the promised land that awaited us now that “freedom” was finally upon us. Of course, such complicated concepts were far beyond my understanding. At seven years old, I reveled in the adventures of Kevin McAllister in Home Alone and dreamed of Coca-Cola and the biggest pizza that money could buy.

One day in September, not long after, I would watch the live broadcast of the World Trade Center twin towers collapsing on that same TV screen. A highly symbolic icon of capitalism and of “the free world” was caving in under the disbelieving eyes of billions of people. No matter how far away we might have been geographically, 9/11 became for my generation what the fall of the Iron Curtain had been for my parents. Cinema had a lot to do with it. This was our first encounter with History, fittingly mediated on a screen. Skyscrapers that I had discovered through the eyes of Macaulay Culkin in one of his New York adventures (from Home Alone 2, 1992) were now suddenly on fire. Each a reminder of the other, these two images will forever co-exist in my memory.

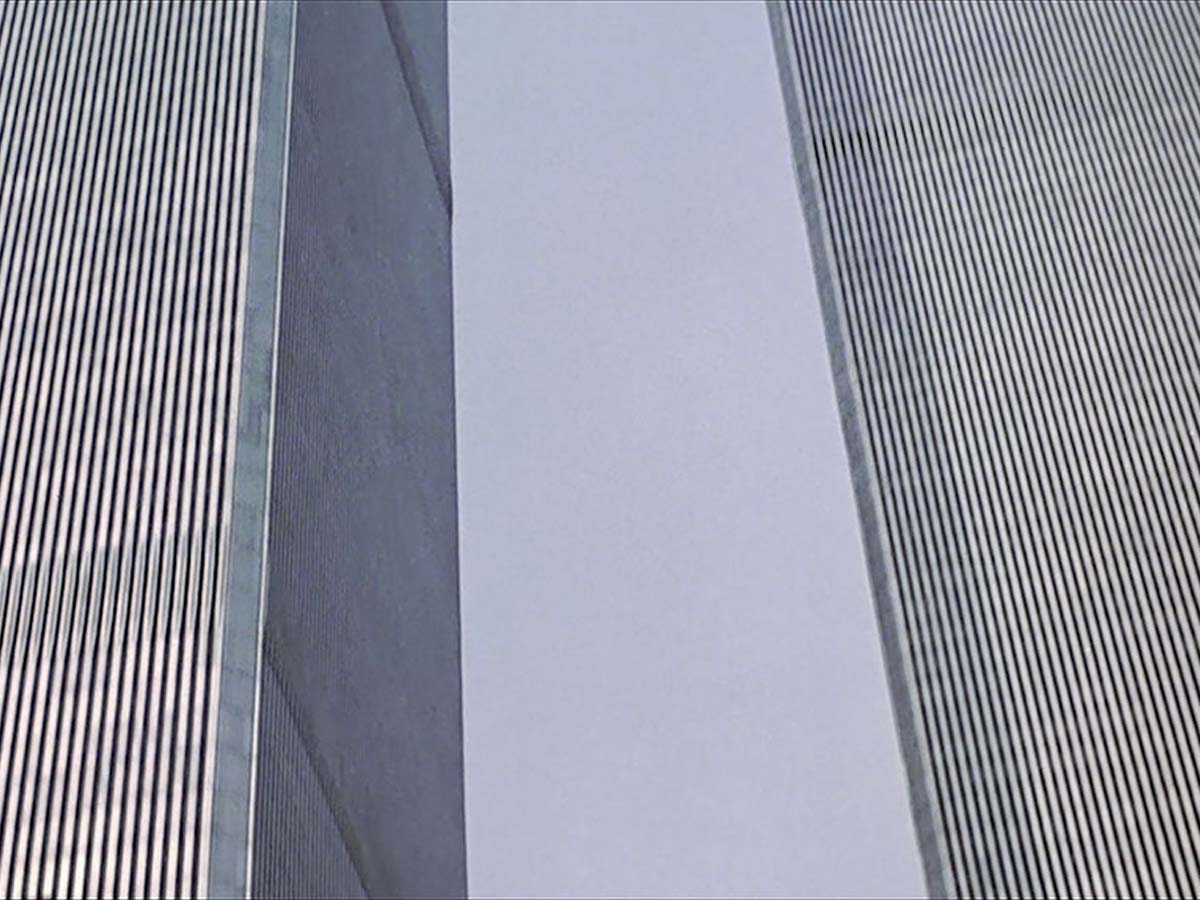

A similar yet more sophisticated process of juxtaposition lies at the core of Christoph Giradet and Matthias Müller’s Misty Picture. Made twenty years after the 9/11 events, their collage film summons the cinematic ghosts of the Twin Towers to create a found footage city symphony that simultaneously reads as an elegy for the place it is centered around.

Avoiding actual footage of the events, the two authors focus instead on excerpts from the myriad of films that portrayed the World Trade Center from its inauguration at the beginning of the 70s until the end of the 90s. Ranging from blockbusters to obscurities, from comedies to dramas, and from thrillers to disaster movies, the images highlight the manifold cinematic stagings of these buildings—from a mere spectacular backdrop to an icon of America’s financial and political power and, more surprisingly, a steel and concrete canvas for speculative destruction fantasies (as is famously the case in the 1998 film, Armageddon).

By isolating these cinematic excerpts from the narrative timelines they once belonged to, the authors are free to focus on the discursive qualities of the images instead. The footage is structured in a series of atemporal loops that follow more or less the same mise-en-scene. Through association, repetition, and accumulation, they showcase the inventory of Hollywood formal clichés that contributed to the creation of the Twin Towers’ symbolic capital, reflecting at the same time on the power of those images to haunt our collective imagination to this day.

Misty Picture opens with a shot in which the camera circles the Statue of Liberty. The ghost-like movement slowly reveals the World Trade Center at night, towering over the horizon, its windows forming bright light patterns. And then again, and again, ten times or more, a slightly different version of the same aerial choreography, starting from the Statue and ending with the image of the towers dominating the cityscape—by day, at sunset, or dawn.

In another sequence, an aerial panorama of the Brooklyn Bridge slowly reveals the silhouettes of the towers in the background of the shot. This composition is also repeated a couple more times from different angles. Similarly, a series of establishing shots presenting New York’s cityscape shows the towers rising in the distance, competing over the skyline with the iconic Empire State Building. Through these emphatic visual associations, we understand the pervasive cultural significance of the Twin Towers—famously the tallest buildings in the world at the time—long before the events that brought them an even greater historical significance.

A constant menace looms over the film; an eerie feeling made all the more pervasive by Chris Jones’ highly dramatic musical score. Heavy clouds gather at the top of the towers as a dark premonition while planes and helicopters fly through the skyline, their trajectory suggesting an imminent collision with the buildings profiled at the horizon. At times, the camera(s) gets closer and closer to the towers in ominous aerial shots. Other shots show the towers suddenly engulfed in darkness.

It’s impossible to watch these images without remembering 9/11. In the fraction of a second between two shots, the subconscious automatically inserts images of smoke and flames, of ruble and despair.

This ghostly potential of cinema has been discussed at length by the medium’s theoreticians, but in the case of Misty Picture, the hauntological quality of the images is underlined by their complete refusal of a linear timeline. Playing a constant game of foreshadowing made all the more uncanny by our knowledge of events that were to unfold, the film shifts freely between past, present, and future—between the real and the fictional.

At one moment, we see a shot of the towers in flames, projected onto a post-apocalyptic landscape, while in the next shot, we find them intact again—a testament to cinema’s promise of endless reanimation. Removed from their initial context, the footage from disaster movies that imagined the destruction of the World Trade Center or other iconic New York City landmarks is invested here with a certain atemporal quality, urging us to wonder once more if it’s fiction that anticipated reality or reality that copied fiction.

Misty Picture will screen at De Cinema on December 21st as part of the short film programme “Postmodern Times” which celebrates International Short Film Day, in collaboration with Kortfilm.be.