This Day Won’t Last

In this urgent diary film about longing for freedom and community, the filmmaker reflects on the individual yet collective experience of growing up queer in Tunisia today. Through personal videos and photographs, the film draws attention to the still-existing Article 230 brought by the French colonisers to criminalise homosexuality.

A colourful piece of fabric on a washing line, blowing in the wind at an otherwise still cemetery. Trapped but ambitious to free itself; surrounded by endings.

Following crises upon crises, for another generation of young people, it has become hard to project into the future; even those in more economically prosperous countries struggle to think about a future at all. For many, dreaming and imagining is now a deliberate act, challenging and political. In Tunisia, with its high youth unemployment rates and its criminalisation of homosexuality (under Article 230, drafted over a century ago by French colonial powers), that act becomes nothing short of radical for the country’s LGBTQIA+ population.

This Day Won’t Last starts with director Mouaad el Salem reflecting on a bad dream. According to his mother and a cleaning lady, it means someone is talking badly about him. It sets up an environment where shame is used to control and haunt people’s everyday lives. Next, a shot of a rainbow, of wide skies reaching much farther than the nearby rooftops—the first image in what will be a recurring evocation of longing for freedom throughout this collage of videos and stills born out of necessity and oppression.

El Salem doesn’t know what he’s going to record this day because he cannot really record: he can never show his face. Even when he shows moments of joy and expressions of identity, he does so either fragmented or veiled, and every seemingly empty corner of daily life and landscape captured is but a proxy for something else. In an interview, el Salem’s collaborator and cousin Nour al Amal says, “In the first phase, I’ve sent Mouaad disposable cameras. Because an undeveloped image is a non-existing image—so we wouldn’t be in danger while travelling with the footage. I was wondering all the time if a film could be a safe space.”

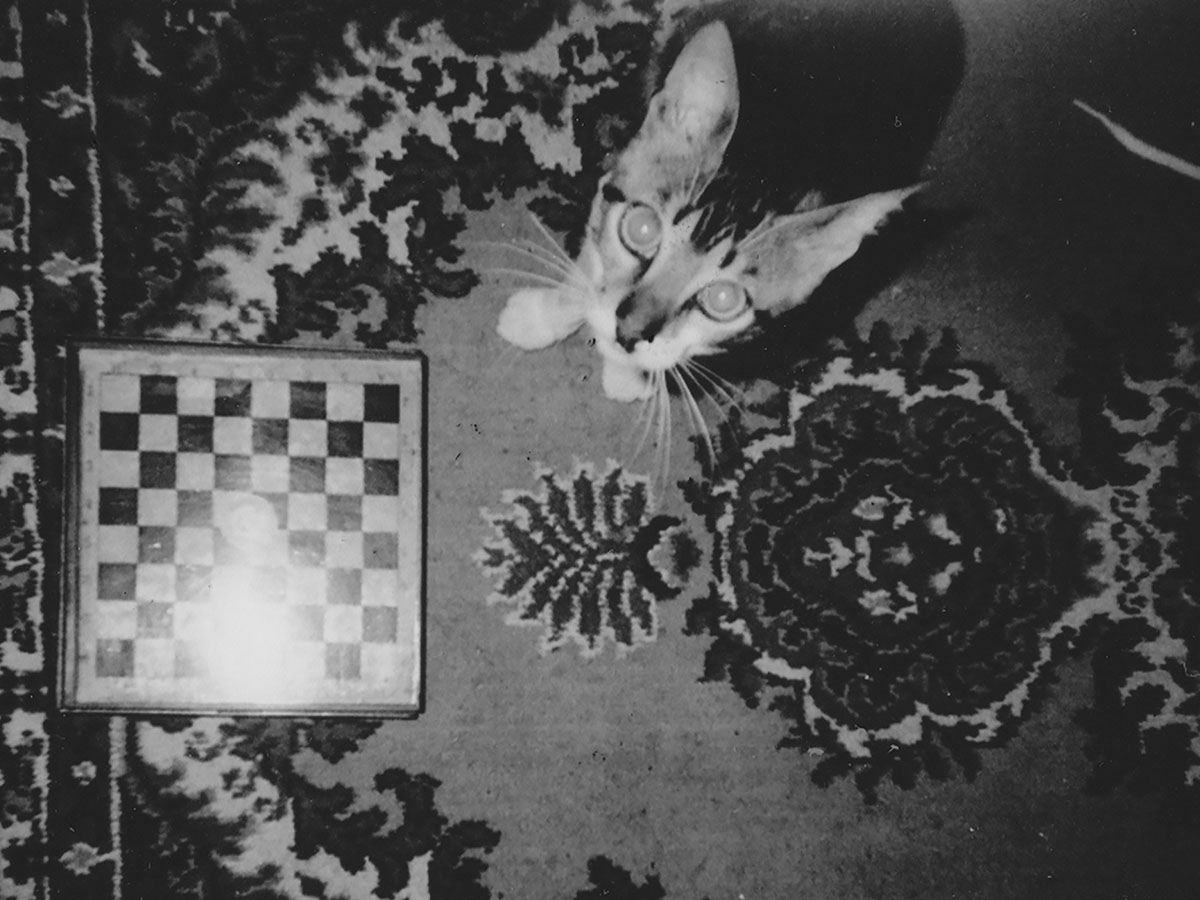

This Day Won’t Last carries risk in every shot; through el Salem’s urgency to film, his constraints of what he can film, the aesthetics of lo-fi phone footage, and the images captured on cheap disposable cameras. Even if the undeveloped film can contain desires and identities without danger, even if these clips do not contain immediate reveals, the images we receive are still constrained and chased by fears and threats. However, they are also an assertion of identity and belonging.

“Tunisia kills our ambitions,” el Salem ponders, followed by photographs of himself, never identifiable, but presenting himself how he’d like to—an ambition. The filmmaker asks what leaving the country would mean, for him and others, and what it has meant for those already gone. He shows us an uprooted fig tree; it dies shortly after it is moved. Considering the film was made before COVID-19 started, watching it post-pandemic adds another layer of meaning. Those wanting to take the risk and leave could not do so anymore shortly after the film’s completion.

Breaking from the more poetic, soft narration that guides most of the footage, el Salem briefly turns to a blue screen—reminiscent of Derek Jarman’s Blue—and speaks more urgently and directly to his viewers about his fears and his need to tell the world his community is being oppressed, to let everyone know that “we are still here.” Because, as he continues, “Gays were also part of the revolution.” They fought for their country’s democracy along with everyone else, and for everyone else, only to be discriminated against through a law designed by forces that colonised the country in the past. This Day Won’t Last exudes the exasperation of having to engage in struggle after struggle; small signs of spirited revolt are enveloped by melancholy and exhaustion—“I think of God, and I say: God, help me bear the pain. God, at least assure me that I will have a future.” A future. Any future. A job, an education. Fatigued, his ask becomes smaller, more individual, and it assumes the pain stays. Tunisia’s revolution is looked upon as the only of the Arab Spring that transformed its country’s system of governance, but with great economic turmoil and entire swaths of the population still persecuted, little optimism remains.

Most of the film moves in quiet personal spheres, but then an image of graffiti spelling “Queers Were Here” indicates a collective struggle, a physical trace of others in search of the same freedom. The image, therefore, signals hope and potential. The film’s last minutes show crowds in protest—it carries higher risk but also visible solidarity, a shared fight, energy, and hope. And then a quiet train journey. We don’t know where to.

In this cyberpunk animation, four creatures wobble like marionettes in a black void. An alien power tries to subdue them; police voices strike as if they were truncheons, but these vulnerable bodies start to fight back.