D’un château l’autre

Spring 2017, during the French presidential election. Pierre, 25 years old and on a scholarship for a prestigious Parisian university, is lodged by Francine, 75, disabled, and confined to her wheelchair. Both puzzled and disoriented, they witness the electoral fair playing out. Both their political opinions and social backgrounds are polar opposites, but they still confide in each other. While waiting for the verdict of the polls, Pierre tries to look after Francine's body and Francine tries to heal Pierre's resentment.

In D’un château l’autre, Emmanuel Marre’s Pardino d’Oro winner at the Locarno International Film Festival, there’s an imperceptibly poignant moment where the depiction of a domestic space encapsulates the political, social, and existential dichotomies that run throughout the film. We see Pierre and Francine. The former is an outcast student from SciencesPo, the prestigious French institution for political studies. The latter is Pierre’s aging and wheelchair-bound landlady, whom he assists regularly. At the beginning of the scene, Pierre puts Francine to bed. She asks him to play a Brahms record to help her go to sleep. Cut to Pierre standing at the window, looking outside. The reflection of Francine lying in bed occupies the left side of the frame. Marre cleverly uses the window to frame his characters in a natural split-screen, creating a filmic space that harbors several binary oppositions. One can even speculate about the political subtext of their positions. But one thing is clear: although Marre’s framing separates Pierre and Francine and serves as a metonymic device to underline their different social realities, they share the same space, not only physically but also emotionally, through their intimate connection that blossoms gradually throughout the film.

The year is 2017. As the French presidential elections approach, the spirit of the times marches at full speed into unrest. Pierre Nisse portrays a young adult whose inner conflicts resonate with those of the outside world. Exasperated trying to fit in with the upper-class frivolities of his university, Pierre looks for answers in the dominant political discourses. D’un château l’autre follows his steps and sneaks into the political rallies of Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen to show us the self-evident artificiality of these gatherings à la Trump. In Macron’s rally at Bercy, the speakers blast DJ Snake & Lil Jon’s hit Turn Down for What, while the zombie-like audience dances along, wearing its most expressionless faces, adorned with shirts, caps, or banners inscribed with the presidential candidate’s name, the newest LREM (La République en Marche) merch. As the Debordian spectacle builds up to its sensational peak, turn down for what, indeed? The political scene is now a dance floor where David Guetta and La Marseillaise fuel the public’s nationalistic sentiments to the same extent: Aux armes citoyens, we are titanium.

Amidst those deadpan faces that feign cheerfulness, Pierre sticks out like a sore thumb. The very incarnation of an observational eye, he fixes his gaze in a way whose meaning only becomes apparent when he tells Francine about his insecurities. Marre incorporates Pierre’s confusion and restlessness into the filmic image. Alternating between the clean precision of the digital image and the nostalgic blurs and imperfections of Super 8, he externalizes Pierre’s fragile state of mind and volatile political opinions. By contrast, given her age, physical condition, and views on life, Francine resembles an anchor that keeps him from drifting away to the farthest shores of the ideological spectrum. Yet, she’s not a figure of stagnation. During her discussions with Pierre, when the latter shares his hostility towards his social environment, Francine tries to encourage him to take action for positive change, to move forward, and, most importantly, to live for himself. Sadly, things are easier said than done.

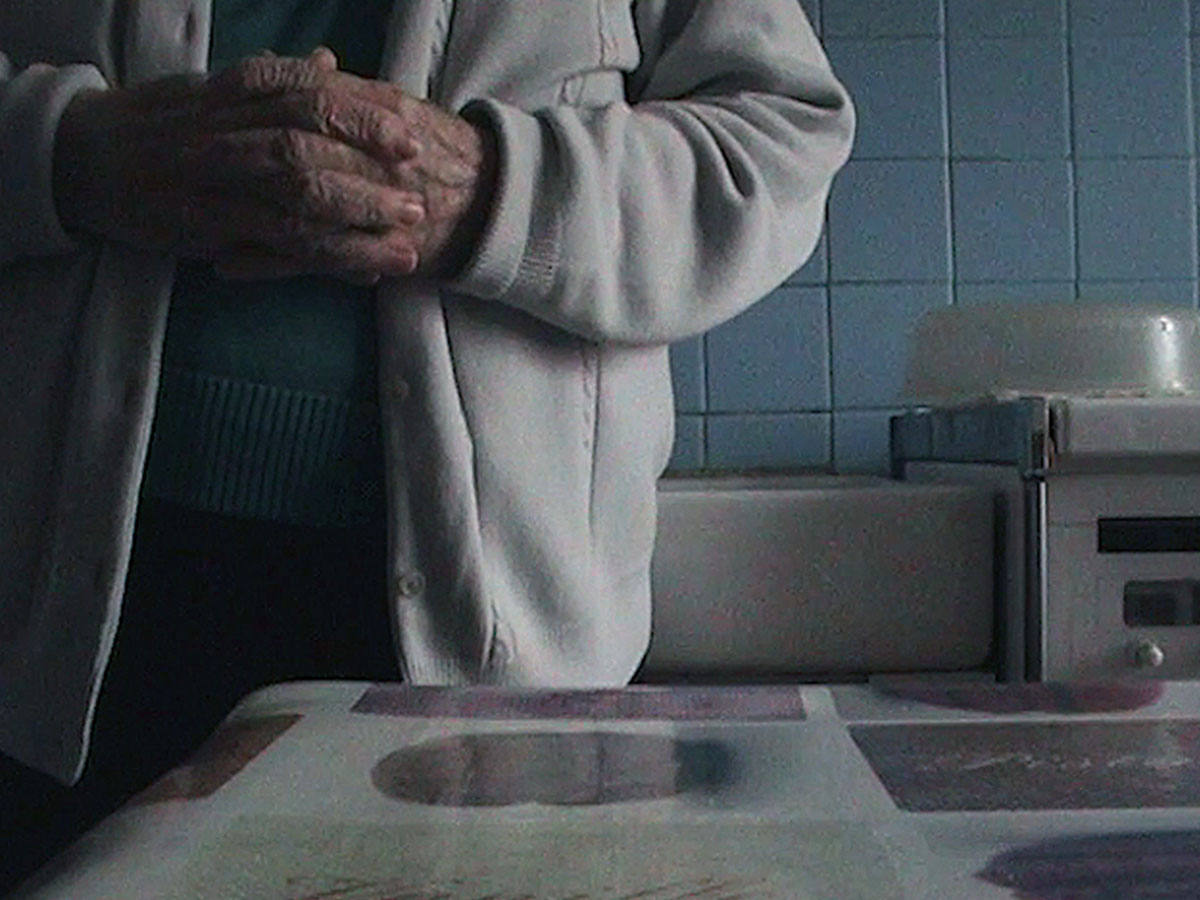

Later on, during a heartfelt scene on the rooftop of Centre Pompidou, Francine opens up to Pierre about her relationship with her children and how her happiness depends on their visits. Although it’s unclear whether Francine’s lines were scripted or not, her trembling voice and falling tears suggest otherwise. Knowing that one of her children is behind the camera, filming this intimate confession, adds much to the emotional weight of this moment. Marre frames Pierre and Francine in profile throughout the entire scene, capturing them as they contemplate the darkening Paris sky. However, at one point, he briefly cuts to a close-up of their hands clasped together before returning to their faces once again. Like the one described at the beginning, this is also a fleeting, easy-to-miss moment in the liminal space between the profilmic and diegetic realities, where even the simplest of gestures—a touch, a gaze, or a smile—is imbued with profound meaning and emotion, thus making it impossible to detach them from either realm.

From Left to Right, from adulthood to old age, indifference to friendship, and personal to political, D’un château l’autre is a film that wanders a lot—not in the least aimlessly, but rather in line with the confusion and yearning felt by the characters. There’s no beginning or end to its wanderings, only serendipitous pauses at these fleeting moments. And when these do happen, they are such a joy for us to watch.

Sitting in her kitchen, Marie-Thérèse realizes she misses everything except her husband. She wanted to be the Princess of Monaco, but after being unhappily wed for seventy years, she must accept she is not.