Gestes du repas

This satirical ethnographic film shows eating Belgians in diverse contexts. Gestes du repas captures authentic moments starring workers, peasants, and middle-class people in their most familiar habitat. Dinner scenes at weddings, funerals, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve portray a country: loneliness and community alternate, just as wealth and poverty.

Seven customers enjoy their lunch in a Brussels restaurant in the late 1950s. Following the footsteps of a waiter who brings them a steak with fries and a filtered coffee, they are introduced to us one by one. The waiter walks from the kitchen into the dining room, from ‘behind the scenes’ onto the public stage. Gestes du repas is a black-and-white film, but we can easily imagine the red-and-white colour of the checkered tablecloths. While those now evoke bygone folklore, the guest taking a deep drag of his cigarette amidst a full dining room is totally outdated nowadays, even unimaginable. With the passage of time, habits are toned down, and even deep-rooted ones may grind to a halt.

In Gestes du repas, Luc de Heusch (1927-2012) shows a series of Belgian eating rituals, from breastfeeding to a funeral dinner, from meals in the factory canteen to a cold buffet held right under a Last Supper at the Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels. De Heusch envisioned his short documentary as a portrait of Belgian society. More than merely a symphony of sipping, smacking, and slurping, a succession of social codes is portrayed in various sections of the population. Rituals interested both the anthropologist and the filmmaker De Heusch, who worked in a time full of upheavals in the relationship between those two disciplines.

Gestes du repas was the first part of a series of films initiated by the Comité international du film ethnographique, founded in 1956 with the French cinéma vérité pioneer Jean Rouch as its secretary-general. The organisation aimed to stimulate and connect human sciences and cinema. De Heusch and Rouch befriended each other during international meetings in that context and appreciated each other as colleagues. It was, however, another traveling companion who came up with the idea for Gestes du repas. The Belgian Henri Storck was never shy to make his voice heard in professional networks and suggested to the Comité that its research should focus on an overarching theme: gestures. Shortly after World War II, while studying art history and sociology at ULB, De Heusch worked as Storck’s assistant on the art documentary Rubens (1947) and the short fiction film Au carrefour de la vie (1948) about juvenile delinquency. A young twenty-something then, when there were no film schools in Belgium, De Heusch found a teacher in Storck. The ‘father of Belgian film’ even became De Heusch’s father-in-law: the anthropologist married Storck’s daughter Marie in 1952. When the Henri Storck Fund was created in 1988 to manage Storck’s legacy, De Heusch became its chairman.

On Storck’s recommendation, De Heusch took a 16 mm camera from Bell & Howell on his trips to the Congo and Rwanda, colonial territories of Belgium back then. This resulted in two films, Fête chez les Hamba (1955) and Rwanda: tableaux d'une féodalité pastorale (1955), and the realisation that the accompanying fieldwork did not really suit him. Unlike his good friend Rouch, whom he first met at a screening of Fête chez les Hamba, De Heusch chose the path of theoretical anthropology and made a clear distinction between this academic work and filmmaking.

De Heusch made art documentaries on Magritte, Alechinsky, and Ensor, but Gestes du repas, his personal favorite, Les amis du plaisir (1961), and even his only long fiction film Jeudi on chantera comme dimanche (1967) can be considered primarily as anthropological portraits of Belgium. Moreover, they cannot be entirely separated from the reflections on Belgian nation-building De Heusch published later, which also found their way into the medium-length documentary Quand j’étais belge (1999).

So De Heusch’s predicate as the ‘Belgian Rouch’ should be taken with a pinch of salt, and not just because of his more theoretical approach. Their film practices also differ considerably. De Heusch was an ardent defender of Rouch’s films and they both recognised the impact of fiction elements in documentaries, but deployed them in very different ways.

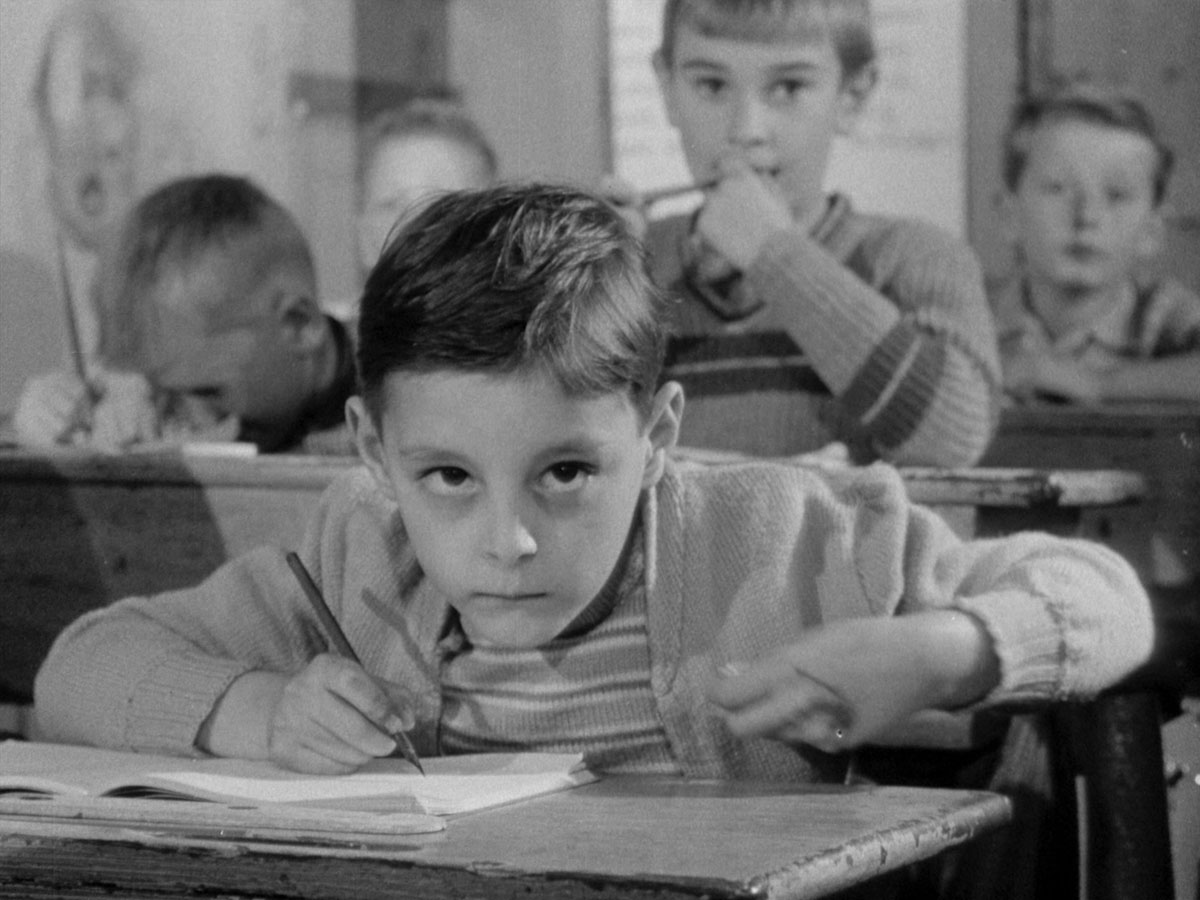

While Rouch explored the dynamics of street encounters with a handheld camera in various African countries or, for the influential Chronique d'un été (1961), in summertime Paris, De Heusch’s films prefer studio staging. In his book Cinéma et sciences sociales. Panorama du film ethnographique et sociologique (1962), De Heusch states that “most of the scenes [in Gestes du repas] were played by workers, bourgeois and peasants who participated in the ceremony of film”. The places where they usually ate, restaurants, kitchens or canteens, were transformed into temporary film studios. The great advantage of the gestures while eating, De Heusch writes, is that they are genuine reflexes that are not altered by cues for the mise-en-scène.

De Heusch introduces the ritual of a film set and staging in an existing environment with existing codes in order to capture their essence. He could have done so as a serious observer, but rather opts for a satirical tone. De Heusch considers filming a “sociological game”. The playful and satirical touch of his films sometimes verges on the subversive. Ideas from surrealism played an important role in De Heusch’s work from the very beginning, both as an anthropologist and as a filmmaker.

When, with some noise, the door of the Brussels restaurant swings open, the seven guests simultaneously turn their heads towards the camera. The mise-en-scène emphasises the group portrait, side by side on a wooden bench, while the timing makes the synchronised gazes undeniably a cinematic gesture. Playfully, De Heusch pairs his cinephile attention to banal acts with an anthropological observation of everyday habits. For this pioneer of anthropological cinema, film is a set-up game that uniquely captures rituals.

Dedicated to nutrition and the human attitude towards “production animals”, this YouTube-found footage collage provides disturbing insights into the behaviour of a Western affluent society towards animal products.