Red Giant

Day and night, a giant sits on a hill, far away from his smaller fellow man. He fills his days organising things, making sure everything is in the right place at the right time. But he himself is usually nowhere to be seen.

A tall, naked Red Giant places a tree here and a house there on top of a grassy plane as if he were an omnipotent being making adjustments to the landscape. But if some say God rejoiced and rested after creating the world, our Red Giant just sits quietly on a hill, observing his surroundings while overcome by a terrible malaise. No one seems to mind or notice him. Time passes, and the giant carries on, waiting for something—anything—to happen.

To be a giant comes with the burdensome nature of giant-ness. Most things look infinitely smaller than you. You move awkwardly, lankily, to not inadvertently step on anything you might not see. Thus this Red Giant proceeds with unsure gestures, sluggishly, as if both depressed and aware of the potential inconveniences his size may cause. Yet, contrary to his stature, a sense of fragility surrounds the giant. Perhaps his nakedness makes him look like a tall, helpless baby. The film’s visual style further underscores this, with the pinkish hues of paint that collect around his small eyes and nose, denoting a form of innocence. The patchy texture of hand-painted animation makes the giant feel alive and fleshy, yet imperfect, raw if you will—tender.

While it could sometimes remind of a child’s drawing (trees are green, round blotches of colour that cover rectangular trunks), the film’s ‘simple’ visual language effectively communicates a profound sense of loneliness and awkwardness. Empty, negative space and large plates of colour allow a feeling of disquiet to seep in, informing on the isolation the Red Giant might feel. The world around him looks deserted, almost unpopulated, and humans are present merely through the traces they leave behind: the outside of their houses, an air balloon idly floating in the sky, some clothes left on a rack to dry. The Sun anxiously burns over this arid landscape. Occasionally, only a moving car might pierce through the apparent standstill. Whenever the humans do come out, they don’t seem to notice the giant anyway. They go about their lives, unknowing and unobserving, with the Red Giant witnessing all their micro-destinies from afar.

Overlapping voices, murmurs, and cacophonous thoughts give the giant a different kind of stress. The more disconnected these sounds are from an actual human being, the more upsetting they become, blending into an incessant, painful white noise. The Red Giant, feeble, alone, and overwhelmed, covers his ears and curls into a foetal position. In this world, the only comfort he seems to have is looking at the sky and the ever-present, ever-burning Sun. Shots of the sky provide a lyrical, meditative tone that seems to soothe the giant, but at the same time, they further contribute to a general sense of uneasiness: looking at the night sky also brings the beautiful yet scary realisation of the vastness of space and the universe. Ultimately, everything becomes too much, and, in what looks like a fantastical dance, the Red Giant leaves Earth to become one with the Sun—merging into a new, red sun.

A ‘red giant’ is also an astronomical term for a star that has entered its final days. Like the giant in Anne Verbeure’s story, it's a star that has reached its breaking point, on the brink of exhaustion. As it runs out of fuel, it gets larger, redder, and brighter. As the sun in the film turns red and the frame slowly gets engulfed by red light (or paint, in this case), we could interpret Verbeure’s short as a creative metaphor and a poetic, non-violent depiction of the inevitable death of the Sun—which one day, in our world, too, will become a Red Giant.

Should that be a scary thought, we can also look at Red Giant as simply a potent study of loneliness and isolation. Verbeure’s film is a great case-in-point to prove that traditional animation is a medium perfectly capable of responding to present times and current themes and maintaining a direct link to contemporary realities. Red Giant’s modernity comes not only from the relevant observations it makes about tired individuals and an over-abundance of stimuli in today’s world but also from its very clever visual language. The film’s most notable and inventive quirk is how, at times, it mimics the digital language of phone-filmed footage, zooms and amateur recordings. Recreating a ‘clips around the globe’ feel, Red Giant ends with everyone looking at the same menacing yet impressive red sun—a beautiful touch of hard-sought togetherness.

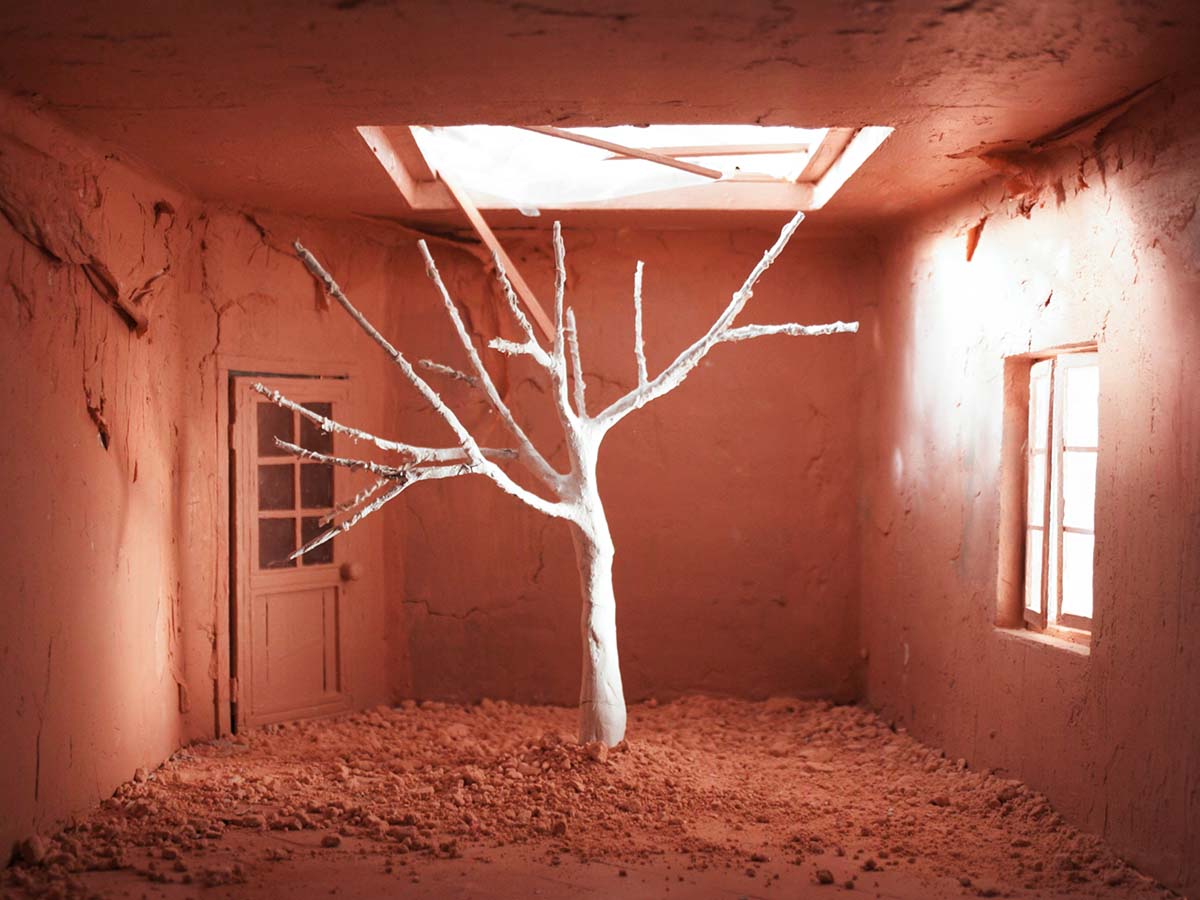

A fictional character’s body is assembled from memories embedded in an abandoned space.